It may be lonely, being in some strange new place in the middle of the night, but nothing is as lonely as going against what you believe to be the strong dark current of your life.

--Bob Saar, In Memory of David's Buick

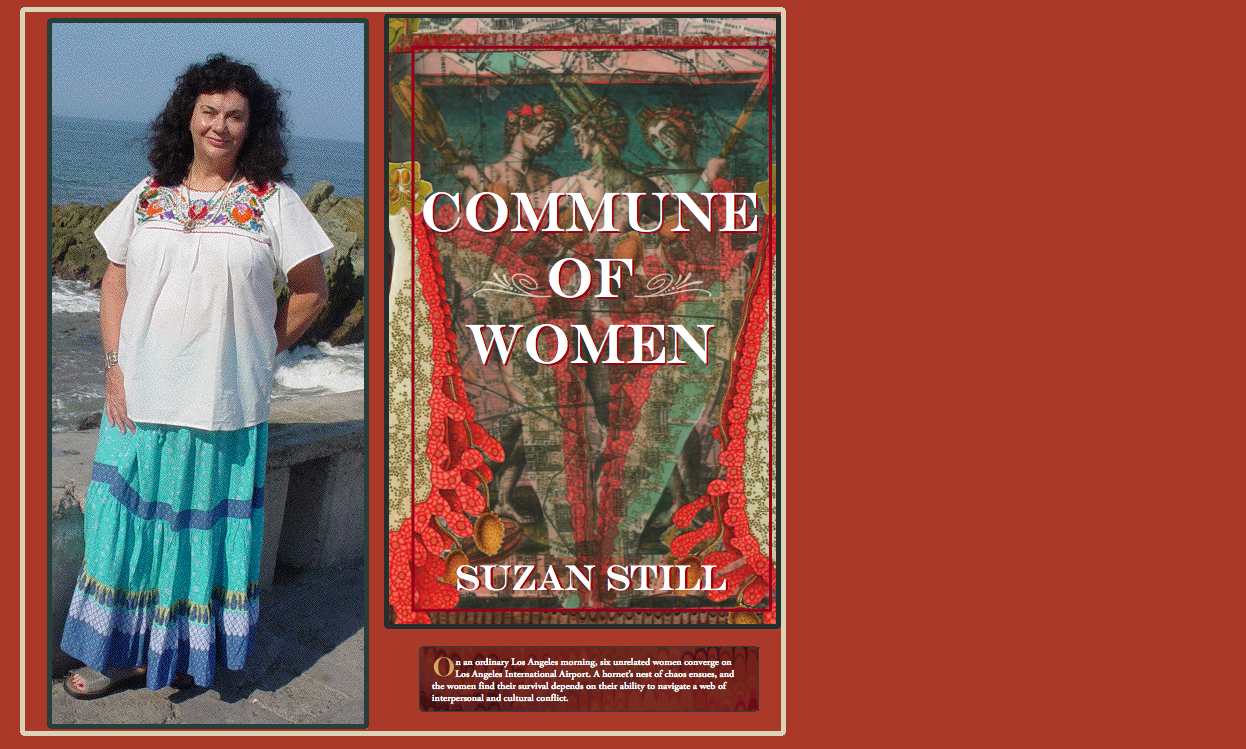

Commune of Women is a novel about six women, trapped together in a small room, who must use their slender resources to survive and prevail by sharing everything: their hope and fear; their food; and their life stories, which grow deeper, darker and more intimate as the days pass.

Sunday, July 31, 2011

Friday, July 29, 2011

In Memory of Richard Chavez

The fight is never about grapes or lettuce. It is always about people.

--Cesar Chavez

On Wednesday, July 27, 2011, Richard Chavez, age 81, passed from this world. Most people know of his brother, Cesar, but Richard was less a public figure than a foundation stone of the movement they both brought into being, the United Farm Workers.

Inseparable, they grew up during the Depression, first on the family farm near Yuma, Arizona and, when that was lost, as migrant farm workers in California’s orchards and vineyards during the 1930s and ‘40s. In the 1960s and for the next three decades, Richard worked full time in the farm worker movement, starting at five dollars a week, as did Cesar and the rest of the movement’s staff. It was Richard who designed the stylized black Aztec eagle that was to become the logo of the United Farm Workers.

There is much being said and written, these days, about unions in general, largely because of the union-breaking efforts currently underway in Wisconsin, and much to be said for both sides of the debate. I cut my teeth on Robert Kennedy’s The Enemy Within, an exposé of corruption within the Teamsters Union under Jimmy Hoffa. Yet, I also have read about the Ludlow Massacre, an attack by the Colorado National Guard on a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal miners and their families at Ludlow, Colorado on April 20, 1914, called the deadliest strike in the history of the United States, in which women and children were killed mercilessly with machine guns and fire, along with striking miners.

I’ve worked hard all my life. I earned my university tuition working in a sawmill as first an off-bearer on the main saw and then a gang sawyer. It’s impossible to explain to anyone who hasn’t done mill work what the conditions are like: the heat in summer and the frigid cold in winter, when snow blows in through the open sides of the building; the cacophony of saws screaming through wood, the clattering of machines and the thunk of logs rolling; the sheer physical exertion of it; and worst of all, the interminable boredom of doing the same repetitive tasks, day after day until the mind numbs. When I began working at the mill in 1964, I earned one dollar an hour.

In 1965, as a freshman at UC Santa Barbara, I took a job as a field laborer, harvesting bird of paradise plants. The day began before dawn and ended after sundown. As the day wore on, the loamy soil worked its way underneath my clothing, where it was annealed by sweat against my skin like fine sandpaper. The heat and humidity were overwhelming. There were no portable toilets and no water available. For this back-breaking stoop labor, I was paid ten dollars a day.

That experience left a profound impression on me. From that time on, I have had nothing but respect and gratitude for the field workers who produce and harvest our food. The union movement may have derailed a few times in its history, in excesses of all kinds. But I will forever be a staunch supporter of the United Farm Workers, who work tirelessly for the rights of people who are sprayed with insecticides, worked in triple digit heat, driven by bosses who think of them as machines or expendable sub-humans, and who go “home” at night to labor camps where they may sleep on the ground or in their cars, only to arise before dawn the next day and do it all again.

I have a passionate regard for the women and men who build and tend our infrastructure: steel workers, carpenters, agricultural laborers, linemen, electricians, welders, cannery and sanitation workers and the like. They put their bodies on the line, every single day that they go to work, and this country could not have been built nor maintained without them. It is in their behalf that I support unions and union products, despite the malfeasance of some union officials.

As I said, I’ve worked hard all my life, but I know I could not do what farm workers do, on a daily basis, month after sweltering month. And I would challenge anyone: go out in the fields for one day. Just one day. Put on you sun hat and stoop beneath the California sun, picking beans or lettuce or grapes for a day. If you make it the full 8 or 10 hours, you’re remarkable--but I’m willing to bet you won’t go back for more, the following day. Most of us, though, would have to be hospitalized, if we tried this.

The movement brought from nothing to become a force to be reckoned with in the agricultural industry, by the gritty determination, expansive vision and deep compassion of the Chavez brothers is, therefore, always going to have my support. We eat food cultivated and harvested for us by these humble people, every single day of our lives. We owe the farm workers and migrant laborers a huge debt of gratitude for our full bellies and for the wide array of foods available to us. So let’s give Richard Chavez our heartfelt thanks for a job well done and a life justly and truly lived in service to his fellow man, and wish him Godspeed, as he lifts off on the black wings of the eagle, to his just reward.

Thursday, July 28, 2011

Better Read that Red

The tyranny of the ignoramuses is insurmountable

And assured for all time.

--Albert Einstein

I'm so excited! I just got my first negative gmail response to Commune of Women! It was so succinct and brilliantly worded! It read, in full: "commie."

Now, I've been called many things in my life, including late to supper, but never a communist. So let me say this once and for all: I am not a communist. Of course, that states the obvious. Denying that I‘m a communist is roughly equivalent to denying that I’m a pterodactyl.

The sender, whose name I shall graciously decline to mention, apparently assumes that anyone who uses the word commune in a title is automatically a communist. By this fascinating logic, books or films with titles like The Scarlet Letter, The Red Badge of Courage, or “Pretty in Pink” become highly suspect, not to mention a band like Pink Floyd or a character like Scarlett O’Hara or a song like “Red Sails in the Sunset,” which one now must concede might be advertising a Russian cruise line. And let’s not even think about what folks like Red Skelton or Groucho Marx were up to!

By all appearances, even the communists aren’t really communists, anymore. The Russians have come out strongly in favor of capitalist, every-man-for-himself down-and-dirty money-making; the Sendero Luminoso or Shining Path, the Maoist Communist organization in Peru, has shifted its activities to smuggling Colombian cocaine; and my Chinese friend reports that Chinese young people are totally indifferent to their government’s propaganda and just want to have the same freedoms and lifestyle we enjoy in the West. I’m sure there are still some diehard commies left somewhere, but--let me say it, again--I am not one of them. Not that it’s anyone else’s business, if I were.

I must say I find being called a commie rather revitalizing. Not, of course, because it has anything whatsoever to do with my actual personal politics, but because it puts me so squarely in opposition to that ancient body of evil, the McCarthyites. I can make light of being this man’s target, but we must never forget that in the 1950s such an unfounded accusation could ruin a career or sterling reputation, and even send someone to prison or drive them to suicide. Blacklisting depended far less on fact than on innuendo, gossip and outright malice.

During the McCarthy era, writing professionals were denied employment because of their real or suspected political beliefs or associations. Artists were barred from working, on the basis of their alleged membership in or sympathy toward the American Communist Party, their involvement in liberal or humanitarian political causes, or their refusal to assist investigations by betraying friendships, by giving up names of others for investigation. Betrayal of one’s principles and one’s friends, and ideological censorship, became the price of a livelihood. Writers, actors, directors, singers, artists and other professionals suffered, not to mention the quality of art and life in America.

I highly recommend the film “Trumbo,” about the life and times of Dalton Trumbo, one of the Hollywood Ten who were blacklisted and denied work during and beyond the McCarthy era. The voices of Joan Allen, Brian Dennehy, Kirk Douglas, Michael Douglas, Paul Giamatti, Danny Glover, Peter Hanson, Nathan Lane and Donald Sutherland read Trumbo’s own writings on the subject, which are sometimes hilarious and sometimes move one to tears.

My gmail detractor has done me a huge favor. First, he’s given me a good laugh. My friends and I will be formulating jokes and good-natured jibes based on this incident, for weeks to come. More importantly, he has reminded me that blind prejudice, ugly bigotry, unfounded accusations and unbidden malice never sleep. Such a person is not only pitiably ignorant of both basic civility and the importance of metaphor, and woefully in need of a real life, one in which impugning innocent strangers does not constitute an indoor sport, but much more dangerously, he is a foot soldier for the tyranny of ignoramuses. As such, he and his jab are not funny, at all. And if we’re looking for what truly undermines the nobility of the American vision, we need look no further.

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Quote of the Day

It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare; it is because we do not dare that they are difficult.

--Seneca

--Seneca

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Quote of the Day

Manifestations from the deepest level often surprise the artist no less than the viewer; he or she knows that the beauty or insight that entered the work of art did so thanks to receptiveness rather than to a fully calculated program of action.

--Roger Lipsey

--Roger Lipsey

Oh Look! What’s This?

I am one of those people gifted with the ability to find another’s psychological Achilles heel, which as a writer is not such a bad thing, I suppose, but can make interpersonal relations difficult. This gift is purely instinctual and spontaneous. I swear to you, there is no malice aforethought. It’s as if I unconsciously scan the energetic lattice surrounding the physical body and percieve the gaping rend there. Suddenly, before I know it, I’m reaching out a finger and sticking it in the hole, exclaiming, “Oh look! What’s this?”

Of course, it is as complete a surprise to me as to the other person, when they instantaneously recoil, shrieking, “Oh my God! Don’t touch that!”

We leap away from one another: they staring at me wildly, as if I were a sudden epiphany of Wickedness, and me shaken, all wounded innocence, like a speckled pup that’s been kicked. I am left bewildered, saying, “What? What??!!” as they back cautiously away, holding out their hands toward me, index fingers forming a cross.

This ability is not exclusively a human trait, either. Puppies, as many can attest, have this gift to an extraordinary degree. When my Rotteweiler, Grafen, was a puppy, about the size that his head is now, he revealed his secret identity as a carrier of this dubious ability.

My husband, David, had a collection of vintage fedoras of which he was justifiably proud, since he looked like the French film director Louis Malle in them and was, in fact, mistaken for him in Paris, while under brim. I, meanwhile, had a pair of Yves St. Laurent gold kid high-heeled sandals--I confess, an unconscionable number of francs, at Rive Gauche--which I kept enshrined on a tall wooden stool in my closet. Before he was even half the size he is now, Grafen had reduced these favorite items to rags. It is a testament to the adorableness of puppies that he survived these ravages.

My friend Bill King owned an art gallery where I used to stop on my way home from town. Bill would pop me a Budweiser and we’d sit in the long, ramshackle, sloping gallery space and talk art. He had, among many other fine objects in his personal collection, a small cinnabar lacquered elephant, about five inches high, which always delighted me.

“When I die,” Bill said, “you’ll get that.” And when he did, I did.

The elephant was my delight. I kept it close to my work spaces and I suppose, although I wasn’t thinking in those terms in those days, it was a kind of totem animal to me. I determined that if there were ever a fire, it would be the first and only thing, besides the cat and dog, that I would rescue.

Then, one afternoon, my friends came to call, bringing their 10-year old son, Ted. As I sat in the garden chatting with the parents, Ted disappeared into the house to explore. About three minutes elapsed. Suddenly, there was an horrific crash.

We raced into the house, to find the cinnabar elephant in smithereens on the floor. I was stunned. His mother was stunned. His father, too.

“It fell,” said Ted.

Now, if that elephant had weighed 20 pounds, it might have made such a noise, in its death throes. But as it was small and weighed no more than a pound, at most, it was obvious: the elephant had not fallen--it had been hurled. With great force.

I gave Ted that look that people sometimes give me, as if next he might swivel his head around backwards, or vomit on the bed.

“Was it valuable?” his mother asked weakly.

“Believe me,” I said, “you don’t want to know.”

Ted is now married, with children of his own. Mercifully, he lives in a foreign country. I have always had tremendous respect for that kid. In three minutes flat, he ferreted out and earmarked for destruction, from among what I admit is an embarrassment of objects, the single most beloved and precious item in my possession. That’s impressive, by any standards. If there are standards, for such phenomena.

People like Ted and me could be thought of as Agents of Karma. A small, covert band of souls placed on the planet to sniff out and expose Attachment. And in my case, at least, to try to convert this uncanny and ungainly sensitivity into art. It’s a tough job, but someone’s got to do it.

Monday, July 25, 2011

Quote of the Day

First they laugh at you, then they ridicule you, then they fight you. Then you win.

--Mahatma Ghandi

--Mahatma Ghandi

Sunday, July 24, 2011

Quote of the Day

Once you make a decision, the universe conspires to make it happen.

--Ralph Waldo Emerson

--Ralph Waldo Emerson

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Friday, July 22, 2011

Brick by Brick

Chaos demands to be recognized and experienced before letting itself

be converted into a new order.

--Hermann Hesse

One of the things that excites me about being a writer is that it requires a long view of the human condition. All those required university Humanities and science courses--history, philosophy, literature, languages, psychology, sociology, ecology, biology, etc, etc, etc—have converged in my brain and reveal themselves to have actual relevance to the real life process of writing. I stand at the confluence of these separate streams, where they mingle and merge, and dip up the result in my cupped hands, and a character is born, or a scene is set, or a tragic narrative trajectory is launched.

We are living in interesting times. My neighbors, husband and wife, just got back from Tennessee, where, as volunteers, they were helping to clean up the devastation of a tornado. They described how brick houses were simply torn asunder, and a trail of loose bricks was laid out for a quarter mile beyond the house sites. This has become, for me, a metaphor for the larger chaos that seems to be ripping the world apart.

It doesn’t really matter what you investigate. Stand outside, turn yourself to any point in the compass, walk less than a mile, and you are likely to find a problem: a polluted creek, potholes in the road, a skulking teenager, or trash thrown from a car window. Multiply these minor problems by the infinitude of their fellows, add large dollops of government corruption, corporate greed, ecological cataclysm, religious intolerance and incessant warfare, throw in a few solar flares for good measure, and you have a recipe for a world consumed in chaos. In a way, it’s a writer’s paradise. One need never want for a topic, a plot, an archetypal Bad Guy or an opportunity for dark humor.

Call me old-fashioned, but I’m of that antique persuasion that writers have certain obligations that might be called didactic. The entertainment value of writing is always going to be a primary factor. That’s why readers gobble up The Da Vinci Code and eschew The Dictionary of Finance and Investment Terms. Nevertheless, it behooves the writer to consider whether the reader will put down the latest read as a human being expanded by knowledge and fortified by a higher spiritual vision, or as a troglodytic brute that craves more violence, sexual dysfunction or racial and gender divisiveness, or a passive, apathetic citizen overwhelmed and undone by literary pessimism.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not advocating censorship here, just a demonstration of what it means to be truly and deeply human in the best and highest sense. Perhaps no one has expressed this better than William Faulkner, in his 1950 Nobel prize acceptance speech, in which he sums up his “life's work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before.” One paragraph is particular states the case, and I append it here, in full:

“Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only one question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid: and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed--love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, and victories without hope and worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.”

Let us return to the metaphoric brick house of human culture. Surely, we are witness to a time when our old sense of the world is being torn asunder and strewn across the landscape in terrifying and life-threatening chaos. Yet, with Faulkner, “I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet's, the writer's, duty is to write about these things.” It is our job to find those scattered bricks, collecting them from the fields where they lie not just fallow but damaged and useless, and to build, brick by brick, word by word, a new edifice to serve the greater good and to demonstrate to future generations that we were not just people of the glands, but people of the heart.

In the words of J. B. Priestley, "No matter how piercing and appalling his insights, the desolation creeping over his outer world, the lurid lights and shadows of his inner world, the writer must live with hope, work in faith." It may be that this chaos to which we are all witness may be a necessary leveling; a reculer pour mieux sauter. In any case, the mess has to be cleaned up, just as my neighbors have demonstrated. So we writers must decide at the outset, before the rebuilding starts, if we are mere sensationalists, leaning up slipshod shelters that will not withstand the first storm, or honest masons, stacking and mortaring our used bricks just and true, not for the sake of enlightened self-interest, only, but for future generations to shelter in, as well.

We are not simple beings. We have all drunk at the confluence and have carnal knowledge of life in its infinite variety, horror and beauty. We cannot claim ignorance. If we fail in our task, it will be a failure of choice; a failure to imagine what is best and brightest; an embracing of sloth, that deadly sin that involves emotional and spiritual apathy. We can’t alter the fact that we live in a time of hurling bricks and stormy chaos. But the building of the new order from the remnants of the old is all ours and a task worthy of contemplating, every single time we sit to bond one word to another.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Quote of the Day

Love of our neighbor in all its fullness simply means being able to say to him: "What are you going through?"

--Simone Weil

--Simone Weil

The Dragonfly Whisperer

I am truly blessed to have as a dear friend The Dragonfly Whisperer, who is a reverend, Reiki master and spiritual adviser, as well as the creator of the website A Gossamer Heart:

Dedicated to the healing of the wounded soul, this site is a treasure trove of information and inspiration, offering prayer, support and healing practices, as well as links to many organizations focused on specific diseases and conditions. I hope you will take the time to check it out. Be sure to follow the link to her blog, as well, where you will discover that The Dragonfly Whisperer is a talented and inspiring poet, in addition to her other amazing abilities.

Also, she is a maker of marvelous inspirational videos. Her 59 Youtube videos have been viewed by over 60,000 people, worldwide. You can view them at:

With the world passing through an unusually rough patch in its history, when greed, corruption, and violence and unkindnesses of all sorts beset it, it’s so refreshing to know that there a people out there selflessly giving of their energies, for the healing of the planet. Thank you, Dragonfly Whisperer, for the overflowing generosity of your spirit.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Quote of the Day

Some say that art is a complicated way of saying very simple things, but we know that art is a simple way of saying very complex things.

--Jean Cocteau

--Jean Cocteau

Monday, July 18, 2011

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Quote of the Day

If you asked me what I came into this world to do, I will tell you:

I CAME TO LIVE OUT LOUD.

--Emile Zola

(Celebrating the "birth" of Commune of Women, which officially launches into the world at 7:30 AM PDT, July 18th!)

I CAME TO LIVE OUT LOUD.

--Emile Zola

(Celebrating the "birth" of Commune of Women, which officially launches into the world at 7:30 AM PDT, July 18th!)

Saturday, July 16, 2011

Join the commune!

This is what I mean by "Join the commune," an exhortation I've used in several interviews pertaining to Commune of Women:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Pu0Fn1oRN4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Pu0Fn1oRN4

Quote of the Day

Life is not a "brief candle." It is a splendid torch that I want to make burn as brightly as possible before handing it on to future generations.

--George Bernard Shaw

(Dedicated to Robert 'Bob' J. Bryson, 04.10.25-07.04.11, who served in the Pacific Theater of WWII and in this country's space program: good neighbor, joyous friend, community servant, loyal citizen and honorable man. Hail and farewell!)

--George Bernard Shaw

(Dedicated to Robert 'Bob' J. Bryson, 04.10.25-07.04.11, who served in the Pacific Theater of WWII and in this country's space program: good neighbor, joyous friend, community servant, loyal citizen and honorable man. Hail and farewell!)

Friday, July 15, 2011

Quote of the Day

If we were logical, the future would be bleak, indeed. But we are more than logical. We are human beings, and we have faith, and we have hope, and we can work.

--Jacques Cousteau

--Jacques Cousteau

Thursday, July 14, 2011

Quote of the Day

When you live at the edge of the mountain, you see the

ABYSS,

but you also see very far.

--Elie Wiesel

ABYSS,

but you also see very far.

--Elie Wiesel

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Quote of the Day

If you do not express your own original ideas, if you do not listen to your own being, you will have betrayed yourself.

--Rollo May

--Rollo May

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

Quote of the Day

In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.

--Albert Camus

--Albert Camus

Monday, July 11, 2011

Archetypal Dimensions

It has occurred to me to write about the principal life theme of each character in Commune of Women. That is to say, each of the women of Commune of Women embodies an archetype, to a greater or lesser degree.

So--what is an archetype? An archetype is a symbol that is universally understood; a prototype. For example, in myths and stories, even across different cultures, the Good Mother and Bad Mother archetypes are readily recognizable in the good (but often dead or absent) mother and the wicked step-mother, the Good Fairy and Evil Witch, or the Wicked Queen and the Good Princess. Other common archetypes in stories are the King, the Noble Knight, the Soldier, the Whore, the Fool, the Orphan, the Teacher, the Priest or Priestess, the Wise Old Woman or Man, and the like. Archetypes give us a basis for understanding the personality and behavior of a character.

A pitfall of an archetypal characterization is that it may become superficial and stereotypical. I’m sure we’ve all read books in which characters are two-dimensional, cardboard people, because they are so predictable. Or ones in which the character is an epitome: noble and courageous beyond the norm, or Christ-like, or debauched, to such an extent that we understand them more as symbols than as flesh and blood human beings. This is so because they so purely embody only one archetype, while to some extent we all, in real life, are mixtures of various archetypal influences and this is what gives our personalities their uniqueness.

One person may epitomize the Good Mother, for example, but secretly cherish that part of herself that is related to the goddess of love, Venus. So we find a woman baking cookies for her home-bound children—while wearing a low-cut blouse and French perfume. Or a man may appear rational, cold and miserly; someone completely unapproachable for any kind of personal warmth—but secretly he is sending money to an orphanage to support needy children, thus expressing his conflict between cold self-sufficiency and the need for intimacy. You might find it interesting to ask yourself which archetypes are blending—and sometimes warring—in your own psyche.

Let’s take as an example one of the characters of Commune of Women, Ondine the artist, who is wealthy, well-educated and -traveled, and who has recently inherited an aristocratic home from her aunt, Tante Collette, on the eastern seaboard of France. Ondine is a dancer as well as a talented artist--beautiful, slender, stylishly clothed, and married to a highly successful and handsome man. What more could any woman want?

And yet we find, at the beginning of Commune of Women, that Ondine is dissatisfied, depressed and confused. For all her good fortune and multiple advantages, she cannot create the pictures or sculpt the sculptures that arise within her. She is burdened rather than inspired by the Artist archetype, creative, passionate and driven, that shapes her personality. What is going on here?

Underlying the dominant Artist archetype is another, that has insidiously taken control: the Neurotic. What characterizes neurosis is passivity and a kind of paranoid and defensive attitude toward external reality. The Neurotic sees life as menacing and influencing them from without and loses sight, completely, of a proactive stance that influences life from within. It is one’s very passivity that makes life appear so menacing, when, in fact, it is largely the projected ghosts of one’s own fears that one perceives “out there.” Thus, passivity swiftly becomes psychological paralysis. This is the state in which Ondine finds herself at the beginning of Commune of Women.

There is only one real remedy for this kind of stalemate: to express in real life one’s own true, inner dimension. In Ondine’s case, this crucial step has been evaded and that evasion has been encouraged by her controlling and judgmental husband. As horrific and tragic as her situation is, when she becomes entrapped in a life-threatening situation, it also offers her a doorway into the greater edifice of her own self. Under the pressure of the very real archetypal presence of Death, she must go within for the resources and courage necessary not only to survive but to break free of the living death she has been enduring for decades.

Will she be able to accomplish this transformation in herself, or will her passivity, in the end, amount to a true death sentence? Therein hangs the tale.

Wednesday, July 6, 2011

Review of Commune of Women

Suzan Still’s experimental novel, Commune of Women, is a remarkable accomplishment. The women of the title are gathered together through sheer accident at Los Angeles International Airport. Strangers to one another, they represent a veritable cross section of humanity—a homeless woman, a psychologist, a former army medic—you get the idea-- they couldn’t be more diverse. Still convincingly speaks in all of their voices, as they, like Boccaccio’s captive group in The Decameron, tell stories to pass the time and keep terror at bay.

Their stories unfold, through four day’s time, simultaneously with another story, that of a young woman separated from her group, the Brothers, in another small room, where she observes events on security monitors and television. Her internal monologue discloses her own past, recounts the lives of some of her troubled band, and muses on her role as the only woman in the cell.

The spare setting—two closed rooms—is offset by the fascinating narratives told by the women, narratives that take the reader to an aristocratic home in France, to war-torn Palestine, to a life of poverty and abuse in the American south. Some of the stories are humorous, some tragic, but all are deeply human. In the present, the women respond to the situation, enduring fear and supporting one another in the midst of chaos.

It’s hard to put this book down. The reader simply must know what will happen to these women. Commune of Women is cautionary tale of our troubled times. One can only hope to behave half as well as these women caught up in events beyond their control.

--Dr. Hope Werness, author of The Continuum Encyclopedia of Native Art

A Gambler's Life

My writer's brain is an over-loaded U-Haul trailer of sights, sounds, smells, textures, colors and vignettes, wallowing down life’s highway. Even unpleasant happenings, like discovering that a half mile of rapids lay ahead, five minutes after donning my first kayak, or being pulled in by Customs for a random inspection, as happened to me on a recent trip to Canada, become grist for the writing mill.

A distinct advantage of this approach to life is that it forces me to write, as some of the load of information must be discharged onto paper or the whole system will collapse, like a bulging moving van sitting lopsided on a broken axle, out on the shoulder of Highway 99. Whether it comes out as a poem, a short story or a novel is immaterial, as long as the urgency is dispelled.

Another advantage of such eclectic observation is that it sharpens my enjoyment of life. No matter where I am or how beset I might feel, there is so much to observe and remember that I’m pulled directly into the moment—and isn’t that just what an enlightened approach to life is supposed to accomplish?

I’ve actually developed techniques for bringing about this kind of immediacy, some of which have proven to be life-threatening--but effective, nonetheless. In fact, one of my novels in progress, The Waiting Stone, pulls its name from just such a circumstance, in which I was spread-eagle on a limestone face, exhausted, starting to hug the cliff with my midsection, and fully aware that thirty feet below me waited strange conical boulders that resembled nothing so much as the lower jaw of a giant, archaic shark. Nevertheless, it was the dry, powdery, scratchy texture and slightly stuffy smell of the moss on which my cheek was embedded, and the fascinating sensation of adrenaline coursing progressively through my body, rendering now my legs, then my arms, and finally my entire torso into a quivering, gelatinous mass, that held my immediate attention.

If it is true that God protects children and fools, then one can readily imagine where I fit in. Or perhaps S/He has written in a special codicil for writers, who--God knows!--deserve some kind of special dispensation, simply for taking on the risks of the creative life. Writing is a gambler’s life: will what one has written--in one’s own blood, it sometimes feels--be worthy of being read? Will it ever find its way into print? Will the critics love it or lob literary rotten tomatoes? Will one be able to sustain oneself financially or end up on a street corner with a cardboard sign, “WILL WORK FOR FOOD?” Will one retain one’s family and friends or will they turn away, shaking their heads and muttering under their breath, as one launches into yet another three-year stint of novel writing, the gleam of a half-baked plot in one’s eyes?

Stay tuned, my friends! Tomorrow is 7-7-11. Behold: this gambler cometh!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)